Across the country, secondary school teachers are engaging in CPD to prepare for the new Leaving Certificate.

The new specifications for subjects are being introduced over a series of five tranches. Tranche 1 in September 2025, Tranche 2 in September 2026, and so on. The full list of tranches and subjects is at this link.

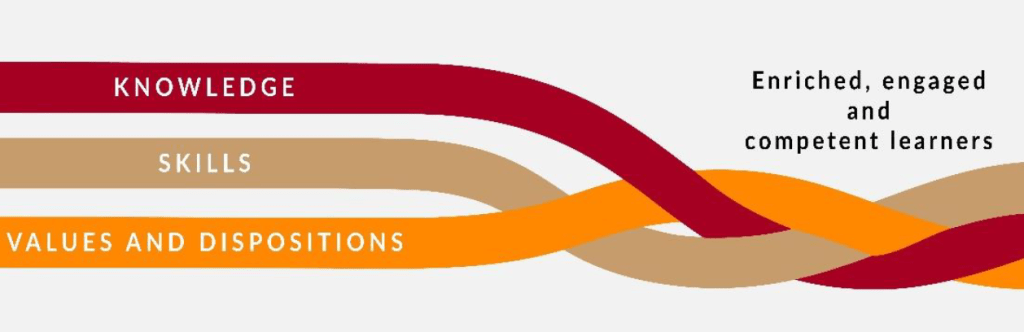

In developing the new standards, the NCCA has sought to underpin the course with three core concepts:

- Knowledge

- Skills

- Values and Dispositions

As a concept, this is something that can be admired. Knowledge is an absolute prerequisite. For any subject a student will need core knowledge in order to complete any tasks, or to claim any mastery over that subject.

Skills are something we all need in different areas. Take music, for instance. You could know all the theory available, but if you don’t know how to compose, play or sing, then there’s a bit of gap in your grasp of the subject.

More interesting for me, however, is that final section. Values and Dispositions. What you end up doing with the knowledge and skills that you have developed over your senior curriculum. There is an obvious challenge for teachers in how to develop this side of the programme that they will ultimately teach in their own classrooms.

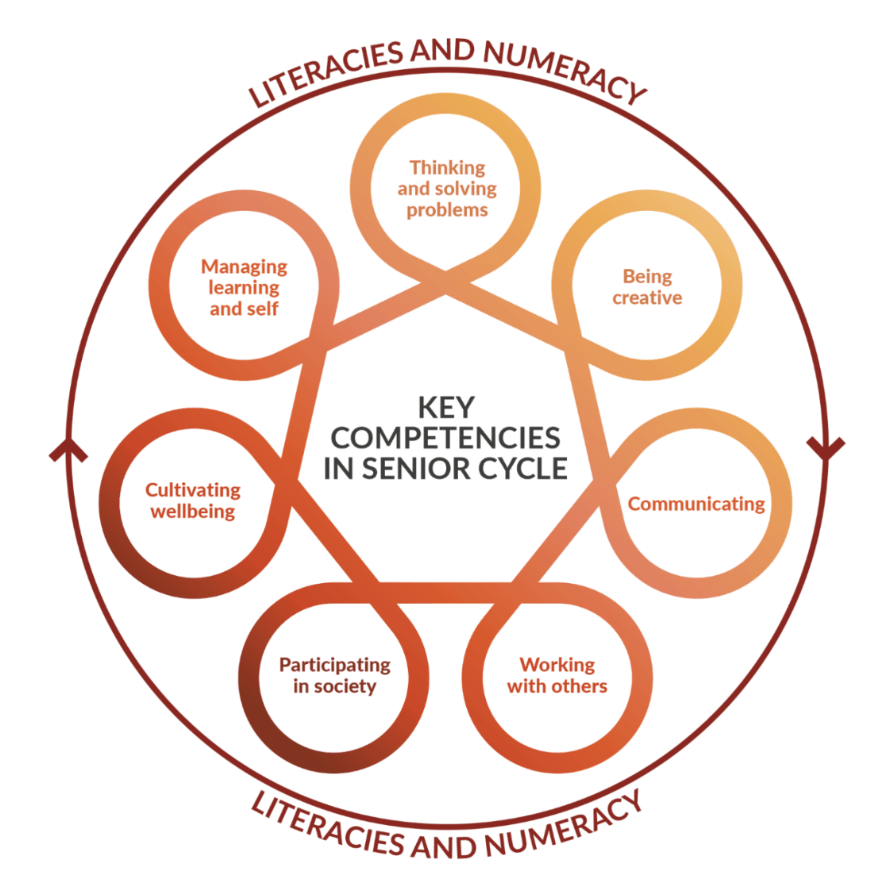

In conjunction with this there is a set of seven competencies. The concept being that these competencies are written in / baked into the syllabus specifications. In effect, they will be an integral part of any given subject.

The big concern, however, that a number of teachers are expressing is in the area of assessment.

Depending on the subject, either 40% or 50% will be assessed as an Additional Assessment Component.

In some subjects exemplars are not yet available, and in other cases the AAC brief has not yet been published. This is leading to a large amount of concern and confusion.

Additionally, there is a concern regarding crowding in the assessment calendar, and of resourcing the production of these AACs. Each AAC will need to be presented in a format that can be graded. Very often this means a digital means will be required.

And, of course, that leads to extra concerns.

Material Resources. Imagine a school with 100 students in leaving cert. Now imagine that each student has to produce an AAC for each of his/her subjects.

That’s 7 subjects (8 if the school has the LCVP programme).

So, 7 or 8 subjects, each requiring 100 students to prepare a project. Most projects will need to be typed, and some will need to be recorded. It’s hard to imagine any school having enough laptop trolleys in order to ensure that this will happen smoothly. Also, imagine the time pressure on some students who could easily have two or three projects due for completion within a week or two of each other.

This article from Emma O’Kelly of RTE proposes that schools need to move towards 1:1 laptops for students.

All well and good, but there is a huge wealth gap in this country. A number of students will not be able to afford laptops in order to meet this need. Remember, this is a country that is constantly breaking its own records for children registered as homeless. Unless the Department of Education is willing to properly fund laptops in schools there will be a gap between the wealthy and those who struggle financially.

Another concern is AI and the influence that it may have on projects.

To what extent may a student draw upon an AI platform in order to structure, research or write a project? At what point can a school say that it will not certify a student’s work? How can we verify the work undertaken, unless it is undertaken in the classroom?

Finally. Is this model of assessment going in the right direction? According to this report from France 24 news, Denmark is setting aside laptops and going back to books.

Nobody doubts that the Leaving Cert needs to be reformed. However, I do feel that we are missing an opportunity by only looking at the structure of the syllabus and assessment. At the moment the Leaving Cert Points System is linked directly to the CAO and college applications. This is a very narrow metric, and something that is putting a huge pressure on students.

Overall, the new Leaving Cert Specifications do offer a lot of opportunity, but a number of teacher questions have not yet been adequately answered.